Augmented Reality in the Physical Retail Space

The high street is in danger, and some stores are turning to futuristic technologies to help stave off the likes of Amazon and JD.com. But what exactly is possible, and where could it lead us?

Retail sales are moving to online, as we all know, and could represent half of the UK retail market by the end of the decade. While there’s something to be said for the halo effect: when a shopper is more likely to spend money in a store after buying products from them online, and vice versa, it’s unlikely to fully make up for the British consumer’s overall decrease in interest in the high street.

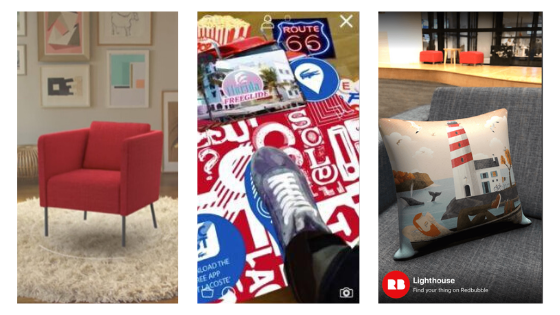

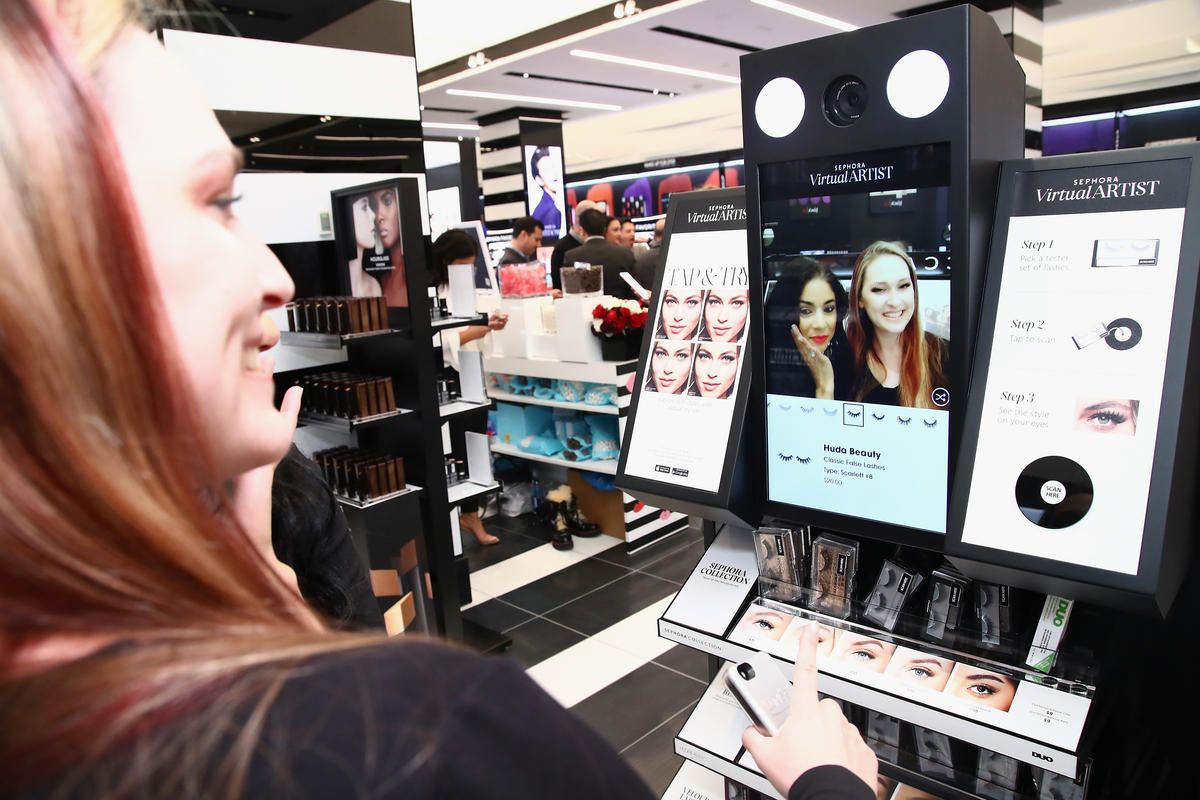

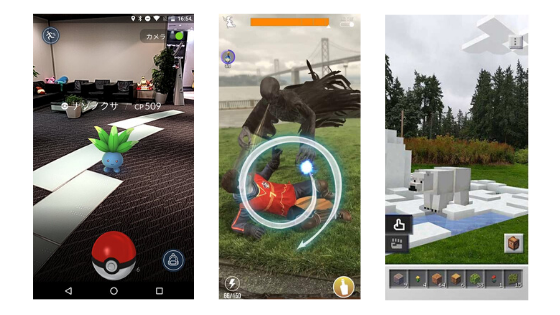

What then can retailers do to make a trip to the shops less of a chore, and more of a day out? Some stores in the UK have tried anything from live music to home baking workshops, but there’s a piece of technology currently being trialled in stores around the world: Augmented Reality, or AR. While it doesn’t have quite the sci-fi legacy of its big sister Virtual Reality, AR is a wider and more versatile medium, ranging in 2020 from smartphone apps to bulky thousand-pound headsets. But it seems that all kinds of industries have been utilising AR technology in an attempt to entice customers through their doors.

Over the next decade, AR technologies are speculated to contribute a £44.4 billion boost to the UK’s GDP (scaling to £1.4 trillion globally), which when combined with VR represents the fastest growth of any industry over that period. By 2030, it’s believed that over 400,000 British jobs will involve augmented reality in some way, leading the charge along with Germany and Finland. Many of these jobs will be in sectors like healthcare, engineering and education, but as the technology develops, more and more retailers will want a slice of the pie.

Augmented Reality has also been tied into the world of geospatial data, with Google’s new AR mode allowing a user to determine exactly where to go during their journey, to supplement the inbuilt compass which is often confused in large cities. The app sends a simplified image of your surroundings to the cloud, which is then compared with Street View imagery to determine your exact location. There is even a safety feature built in, a warning telling users to only use the mode for brief periods to find their bearings, rather than walk around with their phone held out in front of them.

Some independent artists are experimenting with radical ideas that have the potential to do away with some industries all together. The Fabricant is a digital fashion house, one of many popping up across the world who are attempting to sell clothes that don’t exist. At least, you can’t wear them, but your online persona can, providing the perfect counter to the environmental effects of fast fashion. Indeed, last spring someone paid $9,000 for a virtual dress, perfectly tailored, and perfectly carbon neutral.

Combining this nascent shift in shopper’s tastes with comprehensive crowd sourced location data, 5G hyper-fast internet, and sleeker wearable tech (less Microsoft, more Snapchat), we can picture a high-street reinvigorated with a hidden, digital, experiential overlay: impossible artwork, virtual products, but real people.

Header Image: Microsoft Hololens